Blog / 2009 / Photography’s Gift to Art

August 19, 2009

On August 19th 1839, the French government officially declared its patent of Nicéphore Niepce’s and Louis Daguerre’s innovation: a commercially viable chemical process for fixing the images projected inside a camera obscura. One hundred and seventy years later, all of art-kind is still reeling from the announcement.

Where once the goal of art had been to imitate life as faithfully as possible, photography negated that purpose. Though some artists continued on that trajectory, the Daguerreotype (along with subsequent photographic processes) put an end to the all-consuming quest for realism that had plagued Western art for far too long.

And it’s a good thing too! Photography rescued painters from the slavish imitation of life and re-opened creatives to all manner of expressive mark-making and interpretive invention. Because of photography, paintings and artwork of all media (including photography) are allowed to evoke instead of simply represent the world.

What’s more, from the very beginning, photography has been an important tool for painters. By recording background elements and props which the artist did not always have access to in person and by saving models hours of posing, photos make paintings happen.

And it’s that use of photography that really impacts my own work. I maintain that the best portraits are the ones that reveal the way the subject moves and breathes, and it’s impossible to capture that in paint without the help of a modern camera. Photography makes paintings better!

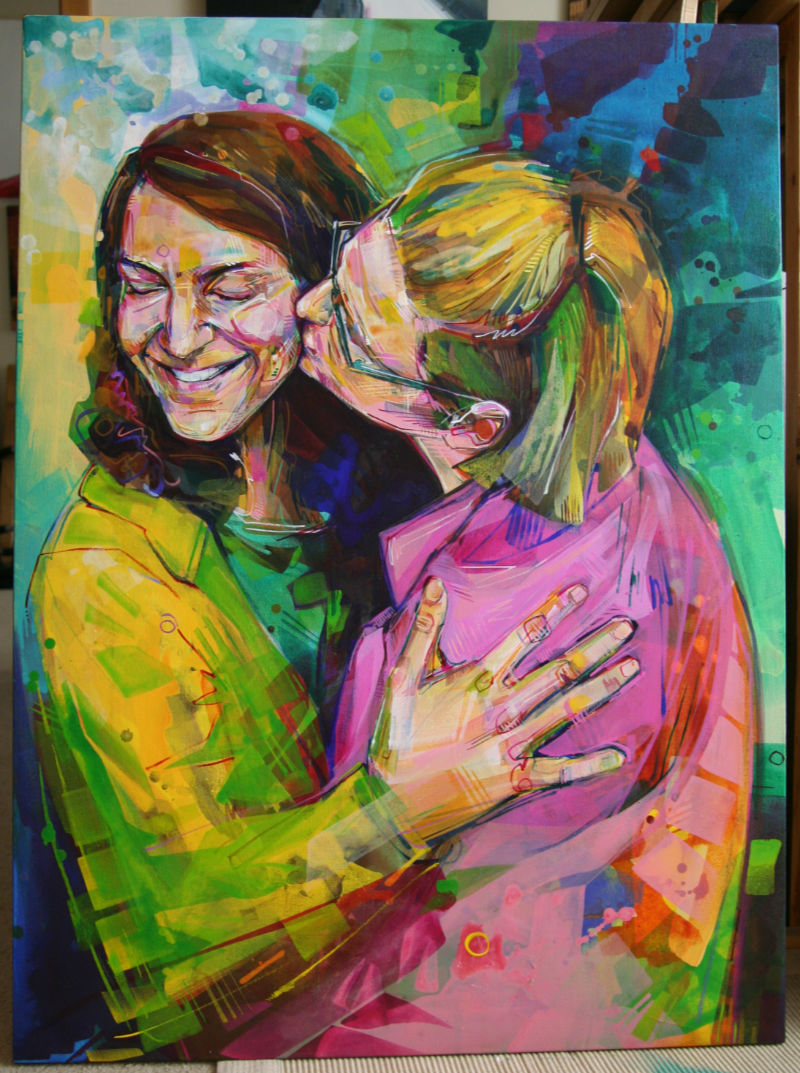

As I set to work on a double portrait of Andrea and Paula for their wedding, I originally thought that I would combine two images from our photo-session.

I liked the idea of them in a dynamic moment of conversation.

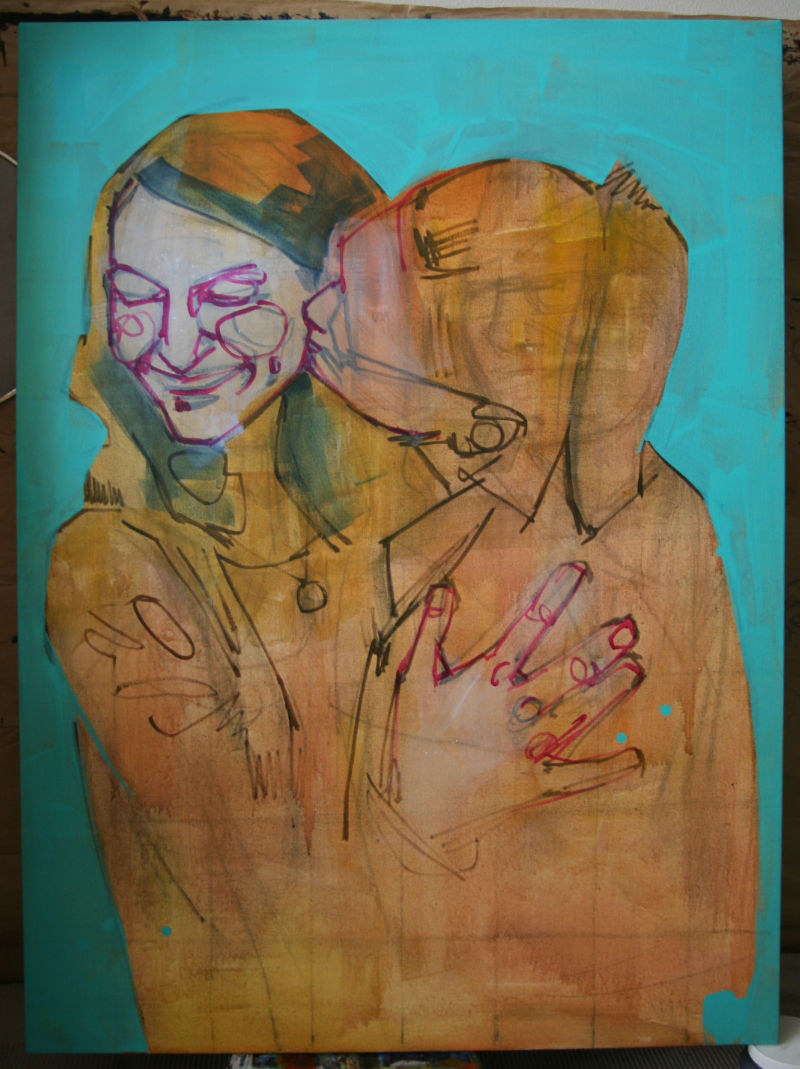

I played around with a lot of different possibilities, sketching in marker and pen on paper as well as mocking up a couple of versions of the double portrait in charcoal on the canvas itself in order to see the possible compositions in full size.

But I was never quite satisfied with my combinations. I found myself returning to this photograph repeatedly. It represents such an easy and natural moment, one that expresses so much about the relationship that I was trying to portray.

As I dove into painting the double portrait using this photo, I was reading De Kooning: An American Master, the Pulitzer Prize winning biography by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan. It’s strange to say, but the book made me paint differently.

I was very nervous about creating a double portrait, and the descriptions of de Kooning’s process helped me overcome my anxiety. I tend to prefer fresh-looking paintings—images that don’t feel overworked—but reading about the abstract expressionist’s manner of building and rebuilding a painting reminded me that a fresh look can sometimes take a lot of work.

Part of my concern over the double portrait stemmed from the fact that I’ve made so few over the years. (This was also one of the reasons why I wanted to make one for Paula and Andrea.)

The first was in 2007, and it was a combination of three separate photos: one of the mother’s face and one of the daughter’s face along with a third of the daughter’s body and arms.

Even at the time, I knew that the 2007 painting looked constructed, but I didn’t mind. I wanted the image of the child to be arresting and the stiltedness of the image added to the effect that I wanted to create.

My second double portrait is from earlier this year.

In that case, I worked hard to get a single reference photo to work from. I learned that it’s much easier to construct and reconstruct the composition in the camera than on the canvas.

That lesson influenced my decision to work with the kissing image of Andrea and Paula. It was important to me that their double portrait have a natural look instead of a fabricated one.

Even so, I was working from a partial photo of the two of them and had to invent Andrea’s elbow.

I got a little carried away in trying to make her arm look right.

Here, I’d mostly resolved the issues surrounding Andrea’s elbow. I was starting to bring in an element from our interview: typewriter keys. There’s a suggestion of them above where their two heads meet.

I used the keys to bring the composition together as a whole.

And, though this has nothing whatsoever to do with de Kooning, I felt a kinship with him as I worked this way—a special kind of freedom about the way I responded to the canvas.

It was as though I had peeled back another layer in my ongoing argument with myself about likeness. Though it’s always important to me (and to my process) that my portraits resemble their subjects in an obvious manner, I’m also keen on exploiting photography’s gift to art.

I don’t see a reason for being too literal even while making a likeness.

Andrea and Paula (The Buccas)

2009

acrylic on canvas

47 x 35 inches

Maybe this post made you think of something you want to share with me? Or perhaps you have a question about my art? I’d love to hear from you!

To receive an email every time I publish a new article or video, sign up for my special mailing list.

If you enjoyed this post, Ko-fi allows you to donate. Every dollar you give is worth a bajillion to me!