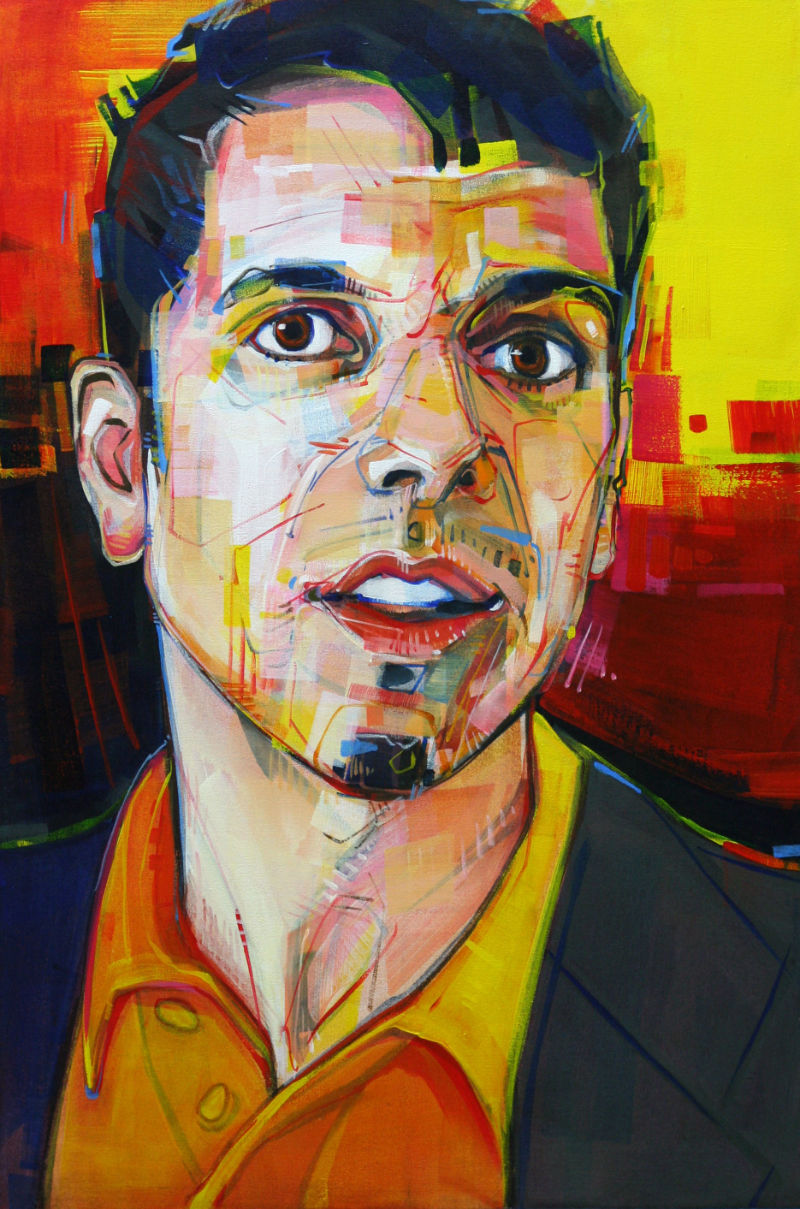

Artwork / Archives / 2006 / Marc Acito

Marc Acito

2006

acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Marc is the author of How I Paid for College and other delightful stories. To learn more about what he does, go to www.marcacito.com or read below for his take on having your portrait painted by me.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Not-so-young Man

Like so many unconventional people, he now lives in Portland. Day after day he stares at the passers-by, who, in turn, gawk at him—his face a traffic light yellow-green-red, his white baker’s jacket an improbable blue-orange-green against a roiling blood-red backdrop. When most people stop to look at “The Little Pastry Cook,” the 1922 expressionist painting by Chaim Soutine at the Portland Art Museum, they’re struck by the turmoil. And who could blame them? Like his contemporary Edvard Munch, Soutine expressed his personal despair with aggressive jabs of paint, as if he were trying to mold the canvas, wrestling it into submission.

But what I see is the love.

There’s an undeniable—pardon the pun—sweetness about the little pastry cook, with his nervous stance and his shy smile. Soutine’s brush strokes may evince his tortured state of mind, but his affection for his diminutive subject gets me every time.

I’ve always wanted my portrait done, which kind of embarrasses me. I mean, only a narcissist wants to hang a painting of himself on the wall, right? But it’s not like I’ve wanted some glorification of myself. Like Soutine’s little pastry cook, I wanted to participate in a painting, to contribute to the process of creating art.

So, when Portland painter Gwenn Seemel approached me to sit for a portrait, I leapt at the chance. Like Soutine, Seemel seeks to elevate everyday people by painting them. “Everyone has got a who-ness that is fascinating,” she said, which is why she’s on a mission to paint every single person in the world. That’s right, every single person.

Since my last name begins with “A” I guess it was my turn.

This is what I love about Portland. It’s so easy to meet screwballs who want to paint every single person. I imagine Gwenn’s text messages:

WAN2TLK?

L8R G2PNTESP

WTF?

Still, having my portrait painted magnified every school picture anxiety I’ve ever had. What’s more, Gwenn contacted me during a binge period of stress eating in which I was stuffing myself like I was being fattened for foie gras. So I looked kind of puffy.

Seemel strived to put me at ease, asking me questions to get me to reveal myself to her. But I’ve had media training. When it comes to interviews, I subscribe to the Miss America method, always giving my carefully prepared response, regardless of the question. As a result, my public persona is a far wittier, more charming version of myself. But I wanted this portrait to capture the real me, that revealed something authentic. So, as Gwenn took the photographs from which she’d later work, I told her how I struggle to keep my equilibrium and about my elusive battle to remain my best self. I shared my fears and how I never feel like I’m enough. None of this is funny. If I were to write about it, I would focus on my more manic tendencies, like the time I went on-line to take a test for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and discovered I didn’t have it. So I took the test again.

“I am asking my subjects to look again at themselves,” Gwenn said, “to really choose who they are, not simply roll along on inertia. I want to say to each of my subjects ‘you are important enough for an artist to paint, you are important, period. Now get living!’”

I wanted that feeling.

Seeing Gwenn’s other work, I already knew how accurately she captures her subjects. She works in a brushy, gestural style, exposing the anatomical structure beneath the skin, which seems to reveal a layer of vulnerability and truth. This made me nervous. If the painting captured the real me, and no one liked it, does that mean no one likes the real me?

The portrait arrived and I saw immediately that Gwenn captured me in my natural state—mid-sentence. If all the world’s a stage, my stage direction would read “Enter talking.” What surprised me, however, is that I looked so...gay. I mean, I’m not one of those guys who particularly values being straight-acting. My feeling is, if you’re having sex with other men, you’re not straight-acting. But, honestly, that insouciant tilt of the head, those soft doe eyes—surely I’m not that fey, am I? I pulled out the soundtrack album of Judy Garland’s A Star Is Born, (the ownership of which essentially answers my question) and was struck by the resemblance. I guess I am that gay. And possibly the secret love child of Liza Minnelli and Peter Allen.

On the other hand, the portrait’s also a little idealized. I’m not being self-effacing here. I’ve seen the original photographs and I look a full ten pounds thinner in the painting. I’m guessing that Seemel knows that it pays to flatter her sitter.

Yet, in the months that follow, a strange and slightly creepy thing happens. Like some reverse Dorian Gray, I actually start to become the guy in the painting. The ten pounds melt away, and I find myself feeling more at ease with myself, more accepting. Like a gardener lopping away branches so that bearing boughs can live, I prune myself.

And I finally understand why I see so much affection in Chaim Soutine’s turbulent portrait. “Pay attention!” Soutine seems to say. “Here is someone who matters, someone who was important enough for an artist to paint.”

Now get living.