Blog / 2021 / The Long-term Effects of Censorship on Artists

April 13, 2021

The flurry of commentary and interest happens in the moment of censorship, right when an institution decides to pull their support for an artwork. That’s when the journalists swarm and the trolls descend; it’s when the venue almost always succeeds in painting the artist as the villain. And if a creative is lucky, this is also when a few people will call or write with a private form of encouragement that is nevertheless precious when everyone else is passing judgment on everything you’ve ever been as well as everything you might become based on a single artwork.

Of course, after the excitement and vitriol have subsided, the institutions get to move on. They are almost always responsible for the misunderstanding that leads to their decision to censor an artist, but that doesn’t matter. Individuals are much easier to blame, and so it’s the artists—and not the institutions—who must carry the burden of the institution’s cowardice.

I’m one such burdened individual. Ever since my anti-Trump art was censored from a show at a public library in New Jersey two years ago, I’ve had to work harder than ever before, saddled by the lie that the institutional representatives told about me to the press, a lie that conveniently made it out like I deserved to be censored. Though I finally got Newsweek to correct the fabrication a year later, I’m not the artist I used to be.

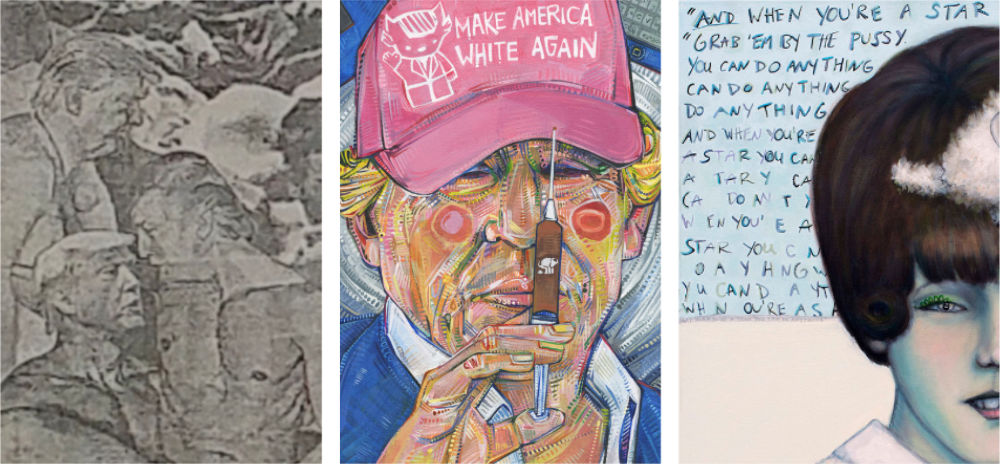

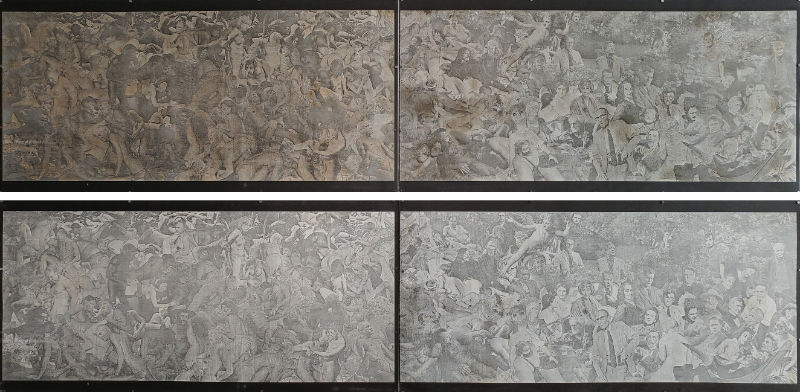

And, from what he’s told me, I don’t think Serhat Tanyolaçar is either. In 2018, this laser-engraved relief print was rejected from a faculty show at Polk State, where Tanyolaçar was teaching at the time. Though the Florida public college hadn’t given faculty any criteria for works that would or would not be included the exhibit, Tanyolaçar’s Death of Innocence was deemed “too controversial” for display.

In particular, a Polk State official objected to the orgy of Trump clones and MAGA leaders depicted in the left half of the piece, saying that, since the campus hosts high schoolers for some programs, the print should not be exhibited. Ironically, Tanyolaçar only ended up teaching in Polk County, which the artist describes as “extremely conservative,” after another one of his artworks made headlines at the University of Iowa in 2014, when the artist was a fellow at the school’s Grant Wood Colony.

On December 5th—the day after the monstrous grand jury decision that allowed Eric Garner’s killer to avoid indictment and eleven days after Michael Brown’s murderer was similarly spared—Tanyolaçar did a public installation of a KKK robe he had constructed from screen prints of newspaper articles chronicling the US’s violent racist history. The impromptu display was in a prominent spot on campus and lasted just four hours. The artist stayed with the work the entire time, available to engage with viewers about the artwork’s purpose, but university officials forced the artist to remove the installation, calling it “divisive, insensitive, and intolerant.”

According to Tanyolaçar, the university’s repudiation and all the press that came with it damaged his career, making the Polk State position one of his few employment options, since Polk was having trouble finding a teacher. Currently, the artist is an adjunct professor and the printmaking program coordinator at the University of South Florida, and, though he’s grateful for the work, the salary is meager. Plus, he’s acutely aware that adjuncts—and especially radical adjuncts—have no job security.Part of the burn of these betrayals is that it’s the supposedly progressive institution of academia that has repeatedly failed to support his work. I know that burn all too well. When a public library and your fellow artists are the ones smearing your reputation in Newsweek, it’s terrifically destabilizing.

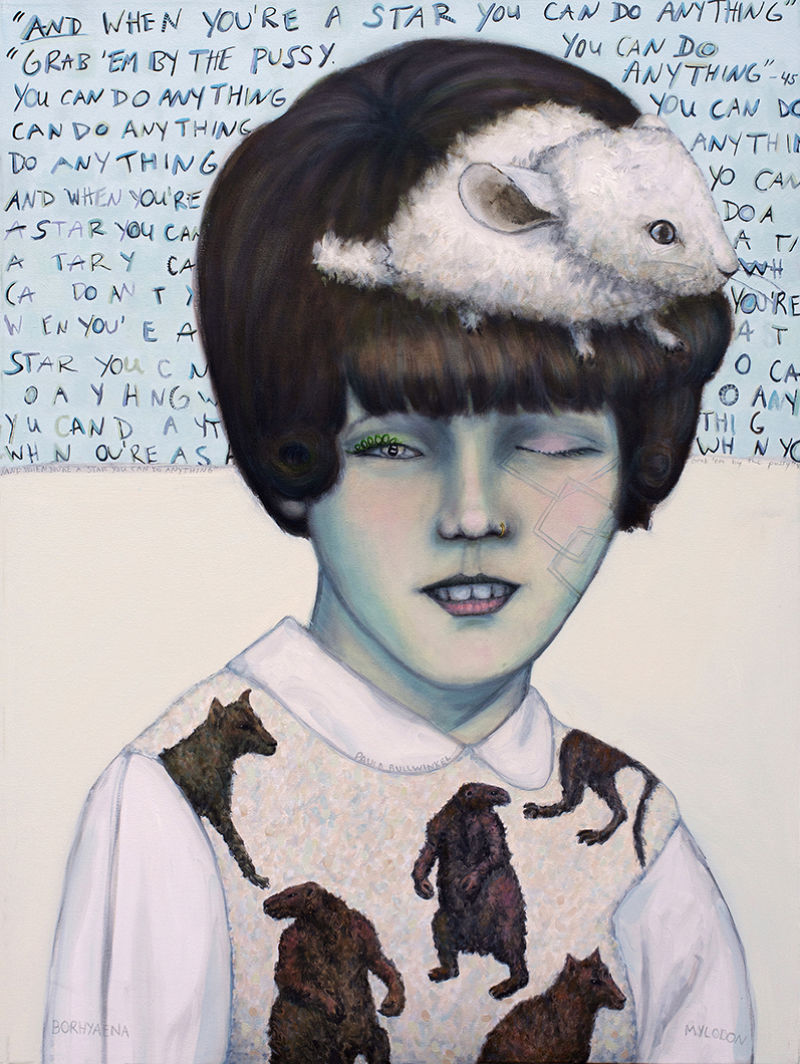

Still, Tanyolaçar’s and my reactions are just one way of processing censorship. Two years after having her art removed from Franklin Crossing, a privately owned mixed-use building in Bend, Oregon, Paula Bullwinkel says that she liked the attention those images got and that she paints with more confidence since the censorship.

The offending artworks were all from a series called 25%! Americans! Approved!—a title referring to the number of people who voted Trump into office in 2016. Like the image shown here, they depict women and rodents, with quotes from the then-president embedded in the imagery. It’s this last bit that got the work censored and, specifically, three words which each measured approximately one inch high in the paintings: pussy, ass, and shithole. A Franklin Crossing representative told the artist that they were concerned that children might see these words, though that worry comes across as melodramatic considering that the rude language had been writ large across the entire United States of America by 45 himself.

A few days after the paintings were removed, they went on display at Bright Place Gallery and then later at Scalehouse Gallery. Bend’s weekly paper featured Bullwinkel’s work on the cover with the word “censored” stenciled over one of the vulgar terms. The article states just the facts without editorializing, but also emphasizes where the objectionable part of this work comes from.

Perhaps it’s this community support that made Bullwinkel’s experience with censorship so much more positive. I admit that I was jealous when she told me about how the removal of her art had affected her. Part of me wondered what I could have done differently to invite this kind of support, but mostly I recognize that it’s the difference of being censored by a commercial entity as opposed to a public one. We both exhibited our art with cowards, but my venue/curators lied about me and then refused to correct the lie because their censorship violated the US Constitution. Meanwhile, the Bend venue didn’t have to make up any excuses for its decision. Plus, Bullwinkel is established in her region, whereas I’ve only been in Jersey for a few years and I don’t live in the community where my art was censored.

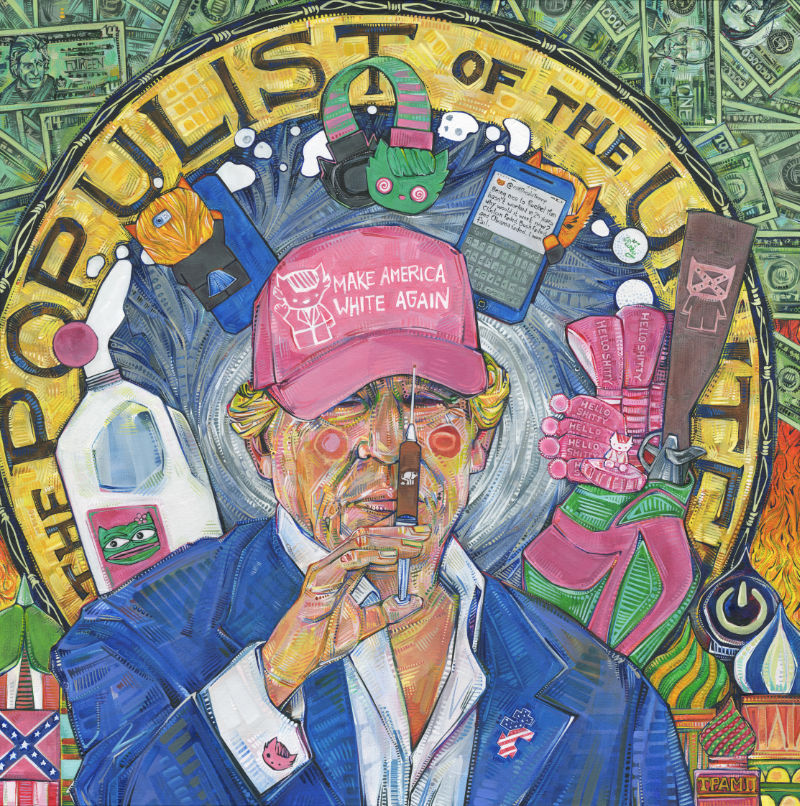

Hello Sh*tty, Available in a White House Near You! (Grab Him by His Pussy.)

2017

acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 inches

In the two years since Studio Montclair Inc and the Montclair Public Library censored this piece, I’ve become neurotic about communicating with venues. I was already meticulously professional in the presentation of my work. Ever since a couple of Jersey public libraries ghosted me in 2016 and 2017 after they realized that the art they’d invited me to exhibit was about queerness in the natural world, I’d learned to head off potential problems. But since 2019, I not only provide an illustrated inventory, I also link the PDF directly to the individual pieces on my site so that the institutional representatives can fully evaluate each image. I tell them the censorship story and explain that I’m not interested in forcing them to show art.

I do everything I can to ensure that the institution understands that they’re welcome to refuse to show my art, but, once they commit to displaying it, they commit to defending it.

It’s hard to say whether or not I’ve lost out on exhibition opportunities like Tanyolaçar has because of negative press, but I’m certain that the censorship didn’t boost my career or my confidence like it did for Bullwinkel. If fact, after SMI and MPL threw me to the wolves, I continued to create political art, but of a very different kind. Specificially, I gave up on adults, turning my attention to children as my primary audience.

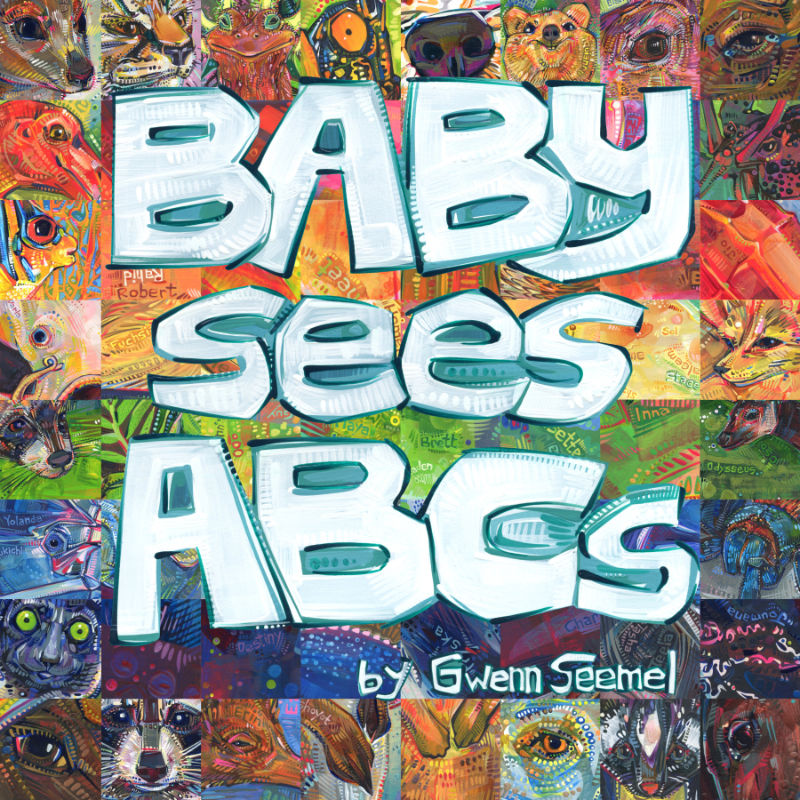

The first work I developed post-censorship is this ABC book. From a passing glance, Baby Sees ABCs doesn’t seem especially political, but on closer inspection you’ll notice a bunch of first names embedded in each illustration. This helps with letter recognition of course, but it also exposes my audience to a variety of cultures early in their lives, stoking their natural curiosity.

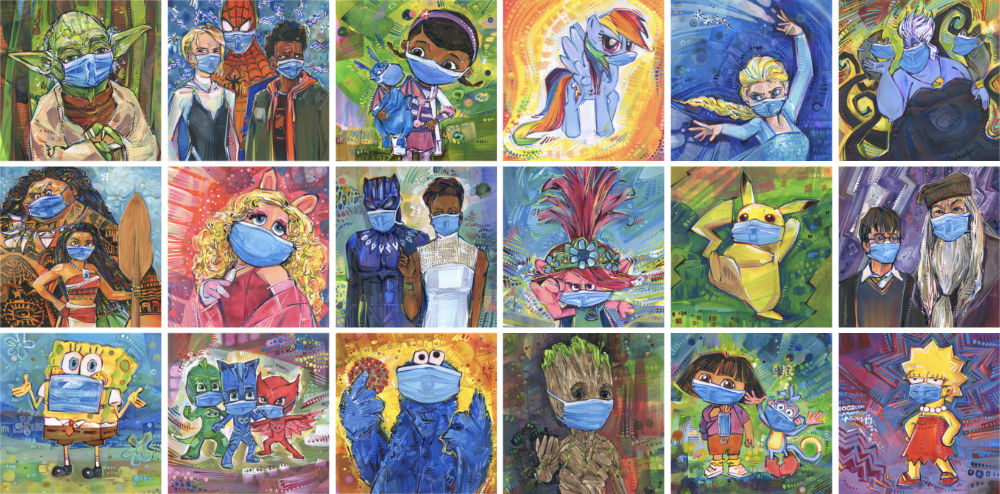

Next, although fan art isn’t my thing, I got really into it last year so that I could leverage the appeal of pop culture characters to make wearing a mask cool. Beyond promoting civic responsibility to kids, my favorite part of Lifesavers Fan Art were the other artists who joined in the effort. They helped me heal from the betrayals of 2019.

In the end, despite the fact that both these child-centric projects make me proud, I still can’t help but wonder what I’d be doing now if an art collective, a public library, and a national news outlet hadn’t all piled on to make me out as the villain.

Considering that the long-term effects of censorship are often that artists stop sharing their work on social media, delete their websites, or become so artistically blocked that they can no longer create, I know that Tanyolaçar, Bullwinkel, and I are all lucky. I just wish we’d been luckier. If venues would take art more seriously—if they’d acknowledge the importance of their role as defenders of free expression—both individual artists and our democracy would be a lot better off.

Maybe this post made you think of something you want to share with me? Or perhaps you have a question about my art? I’d love to hear from you!

To receive an email every time I publish a new article or video, sign up for my special mailing list.

If you enjoyed this post, Ko-fi allows you to donate. Every dollar you give is worth a bajillion to me!